The charm of horse racing lies primarily in the animals that do it—their beauty, grace, power and their degree of class. But there is an undeniable attraction to the colorful human beings that make it happen. The purpose of this blog is to share my stories about some of these characters. My requisites in the selection: I had dealings with them, their antics and accomplishments should not be forgotten, and they are no longer with us.

"Hahhhd dam, Buddy!"

That was his war cry. In a gruff, gravelly voice that rumbled like a freight train barreling over a trestle, that which followed from Warner L. Jones was sure to be either interesting, valuable, or funny…and much of the time outrageous.

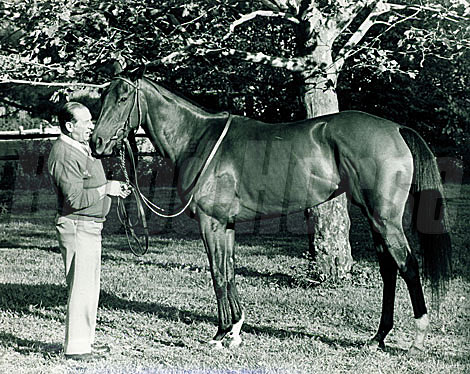

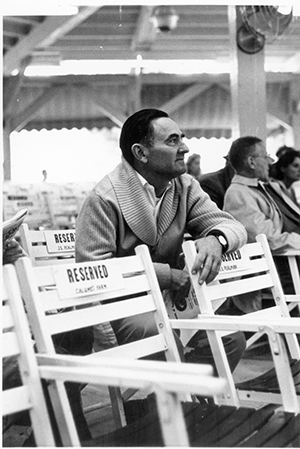

This famous Kentuckian was the master of Hermitage Farm, a major breeding establishment just outside of Louisville. He was a bona fide "drinking man’s drinker" in his day but joined Alcoholics Anonymous in 1964, and never took another drink before he died in 1994. He cut a wide swath before and a wider, more important swath afterward. He accomplished much in both eras, but certainly an incredible amount in his sober years.

A tribute to his charisma and charm was that many, many people thought they were Warner’s best friend. He had several hundred best friends, and I was one. One reason I qualified was that my early years were similarly tumultuous by my own doing.

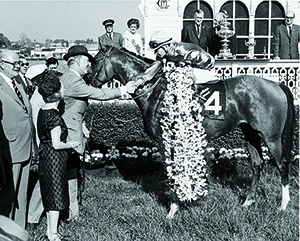

He liked for me to help him on his reserves at sales, meaning that Warner got me to bid on his horses to see that they got to the right "neighborhood." One noteworthy example involved the highest-priced yearling ever sold. This Nijinsky colt out of My Charmer, the dam of Seattle Slew, brought a final bid of $13,100,000. He asked me to bid "up to $10 million." I asked no questions and did it, although he didn’t need me. I had to hurry just to get the opportunity to raise my hand once during this history-making transaction.

Warner made a lot of money, but he did start with some money. He had a pedigree about like that Nijinsky colt. And he came from a background that would have provided a lot of "advantages."

When he was about 10, he was enrolled in Aiken Preparatory School in South Carolina. He had never been away from home in his life, and despite his legendary toughness and outward bravado, he was understandably homesick. One day, he was staring out his classroom window thinking about home and family, and he was overcome with homesickness (a serious malady, as most of us know). Warner started quietly sobbing. A big day student sitting in front of him turned around to look at Warner, laughed, and began taunting him.

"Ooh, just look at the mama’s boy. Him is crying for his mama! Is he homesick for Kentucky?" On and on it went

When Warner was telling me about this incident, I commiserated with him, "Gosh, that was terrible, Warner! What did you do?"

"Hahhhd dam, buddy. When recess came, I grabbed that big son of a bitch and kicked his ass all over that school yard!"

That was Warner Jones: sensitive, but tough.

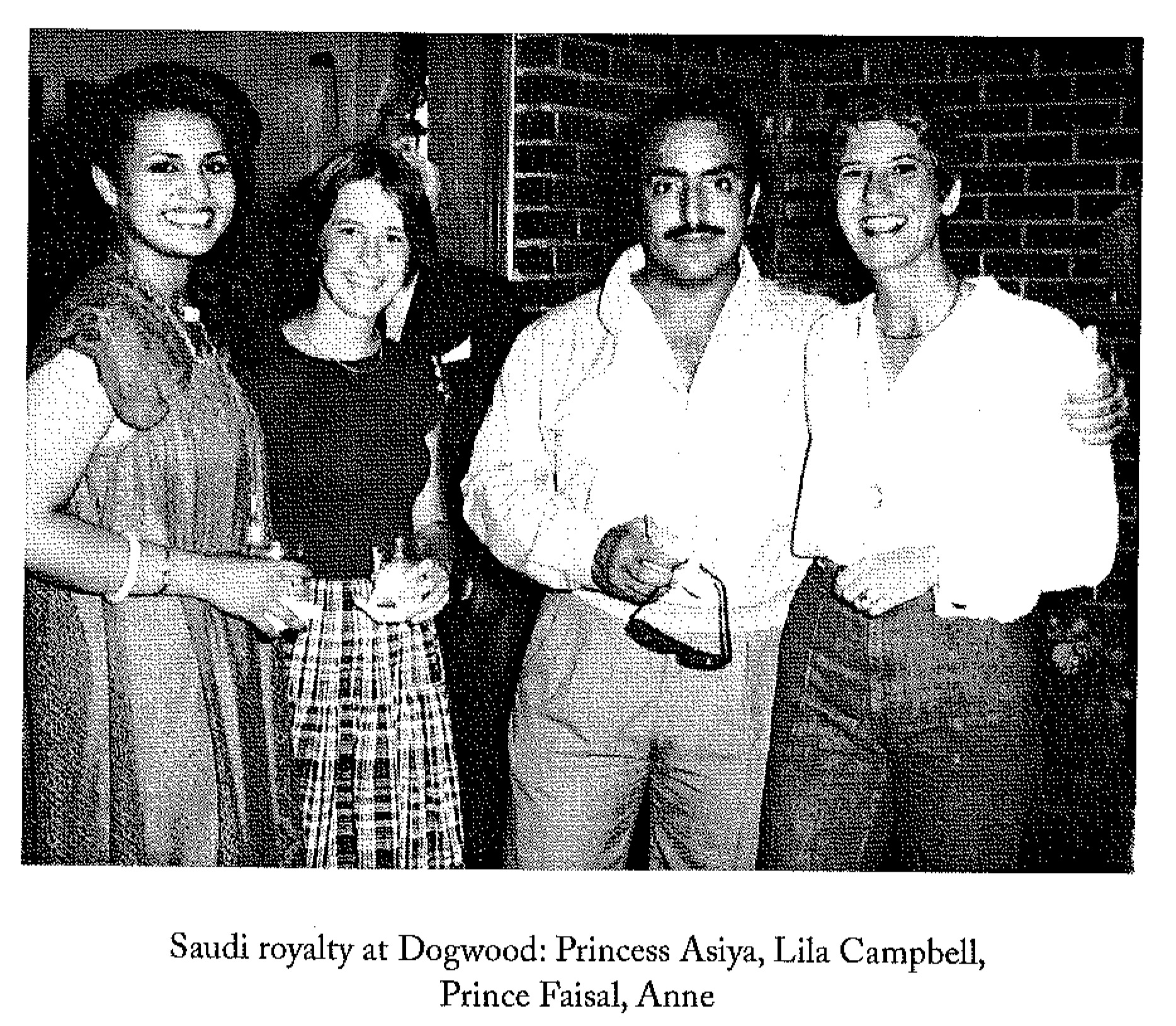

Warner spent much of the year on entertainment and "sales promotion" designed to assure that when his yearlings went to market they would bring good money. In the early '80s, the Arab sheikhs were spending millions at yearling sales in this country, creating a feeding frenzy in the horse business. Every consignor dreamed of making strong connections with this bottomless supply of greenbacks. Gaining direct access to the sheikhs themselves, however, was extremely difficult. These mysterious men of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had zero interest in social invitations.

But each of the Arab princes had at least one bloodstock adviser. Invariably, these were elderly English horsemen of very refined backgrounds—and sporting military rank designations of captain, major, colonel!, with an occasional lord and sir popping up. And these gentlemen were definitely susceptible to entertainment.

The huge and sudden manifestation of Arab interest was an unexpected bonanza to these types. They were not overly busy beforehand, I think.

One of the most important was Sir Hubert Courtland (as we’ll call him). His connection to one of the most powerful and enthusiastic sheikhs did not escape Warner Jones. While his heart was not really in it, Warner and his wonderfully supportive wife, Harriet, invited Sir Hubert and Lady Marjorie for a week-long visit at their winter home in Delray Beach, Florida.

The English couple accepted and flew over to West Palm Beach, where the Joneses met them. The foursome embarked on what was to be a week of pleasant and varied resort activities, with Warner avoiding any hard sell on the yearling crop going to market in several months. Once they had settled in, Warner suggested to Sir Hubert that a round of golf at Seminole might be just the ticket after a long, tedious journey across the Atlantic.

"Do you know…I’ve never had an inclination to take up that game," Sir Hubert told his host.

This was not good news.

"Well then, tomorrow we’ll take the girls and go out on the boat. The king mackerel are running now, and we could really have some fun," Warner offered.

"Oh, I’m afraid not," Lady Marjorie jumped in. "Both Hubert and I are horrid sailors. We get queasy as soon as the boat leaves the dock!"

That night after dinner, Harriet suggested the two couples play a few rubbers of bridge.

"Not much for card games. Never saw the good of it," Sir Hubert responded.

So the first day ended with golf, fishing, and bridge having been struck off the list. Still, there is plenty to do in Florida.

The next morning after breakfast, Warner suggested they all drive down to Gulfstream Park for lunch and racing.

"Oh, really now! This is my vacation to get away from racing," the English guest replied.

Tennis? Didn’t play.

Backgammon. Afraid not.

Sunbathing on the beach, swimming, strolling on the sand? Sir Hubert explained, "Marjorie’s fair skin simply does not permit it. She would be burned to a crisp in minutes."

Now racing, tennis, aquatic activities, and backgammon were eliminated. What was left? Mud wrestling?

That night the thoroughly discouraged, but dead-game Joneses and Sir Hubert and Lady Marjorie went to the Gulfstream Club for dinner (they did eat!). An orchestra was playing. Warner gritted his teeth and asked the very rotund Lady Marjorie if she would like to dance, hoping fervently that this activity would also be unacceptable. No such luck. She graciously took his hand and the couple glided out on the floor, Warner looking as if he could bite a 10-penny nail in two.

About halfway around the floor, the host smiled dutifully at his partner. She wriggled excitedly and gushed, "Oooh, Mr. Jones, this is heavenly. I do so love to dance. Dancing is truly my weakness, my greatest pleasure. I could just go on dancing the night away!"

In telling the story later, Warner explained, "Hahhhd dam, buddy! Every time I’d get tired, I’d think about those million-dollar yearlings, and I just kept pushing that old fat gal around the floor."

More of Cot Campbell's stories are included, among a host of others, in The Best of Talkin' Horses.

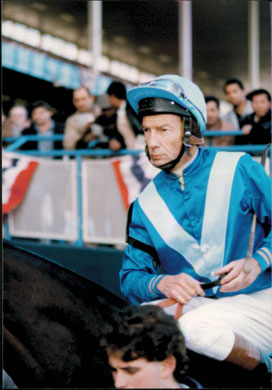

He was

smooth as silk, but on one occasion he did lose his cool.

He was

smooth as silk, but on one occasion he did lose his cool.  The makeup of Lester Piggott would have more to do with his

fanatical determination to win; his ruthless approach to securing the right

horses to do it with; his taciturn, dour, penurious nature; and his completely

independent, mischievous, impertinent demeanor.

The makeup of Lester Piggott would have more to do with his

fanatical determination to win; his ruthless approach to securing the right

horses to do it with; his taciturn, dour, penurious nature; and his completely

independent, mischievous, impertinent demeanor.

One of the leading trainers in North America was a man named Frank Merrill. He had a lot of horses, and he campaigned in Canada in the summer and went to Florida in the winter. He had been sending his client's yearlings to a farm in Ocala for breaking and early training, before he took them over for campaigning. I had targeted Frank as an ideal client for Dogwood

One of the leading trainers in North America was a man named Frank Merrill. He had a lot of horses, and he campaigned in Canada in the summer and went to Florida in the winter. He had been sending his client's yearlings to a farm in Ocala for breaking and early training, before he took them over for campaigning. I had targeted Frank as an ideal client for Dogwood To say there was a great deal of pressure attending this colt's debut is a masterpiece of understatement. The other partners were excited; I was definitely excited, and, of course, I was going to California to see the colt run.

To say there was a great deal of pressure attending this colt's debut is a masterpiece of understatement. The other partners were excited; I was definitely excited, and, of course, I was going to California to see the colt run.